In a recent conversation with Ecuadorian business leaders, a recurring concern emerged: Is Ecuador becoming the Colombia of the 1990s?

The question, heavy with anxiety, prompted reflection. As a regional security consultant, my response may seem counterintuitive: the genuine concern is not that Ecuador is becoming Colombia but that Colombia – and other countries in Latin America -are becoming Ecuador.

This statement is not meant to downplay Ecuador’s efforts to confront organized crime. On the contrary, it highlights a deep, silent, and global transformation of transnational crime advancing steadily throughout the region, reshaping traditional security, governance, and development models.

The Evolution of Organized Crime: From Cartels to global networks

Referring to Douglas Farah’s analysis in The Fourth Wave of Transnational Crime, it is crucial to understand the transformation of organized crime in Latin America. Farah outlines how these organizations evolved through at least four major stages, each more sophisticated and dangerous than the last:

- First Wave (1970–1994): Pablo Escobar and the Medellín Cartel led this Wave, marked by visible violence, large-scale cocaine production for the U.S. market, and brutal territorial control.

- Second Wave (1990–2000): A strategic shift led by the Cali Cartel, characterized by institutional co-optation, financing political campaigns, and corrupting state structures.

- Third Wave (since 2005): Consists of the emergence of the Bolivarian Joint Criminal Enterprise (Empresa Criminal Conjunta Bolivariana) centered in Venezuela, where crime merged with the state, blurring the lines between legal and illegal power and involving groups such as the FARC, ELN, and institutional corruption networks.

- Fourth Wave (current): This hybrid, transnational, and fragmented model is new. Transnational Criminal Organizations (TCOs) no longer operate as traditional hierarchical structures. They function in networks with global alliances that include extra-regional groups like the Italian ‘Ndrangheta, Balkan clans, Turkish networks linked to Erdoğan’s regime, and groups such as the Grey Wolves, who collaborate with both the Sinaloa Cartel and FARC dissident groups like Segunda Marquetalia.

These illegal groups traffic not only cocaine but also synthetic drugs, illegal gold, weapons, migrants, and counterfeit pharmaceuticals to Europe, the Middle East, and Africa. These criminal economies move trillions of dollars, creating a new class of “global criminal corporations.”

Ecuador: An Epicenter In Dispute

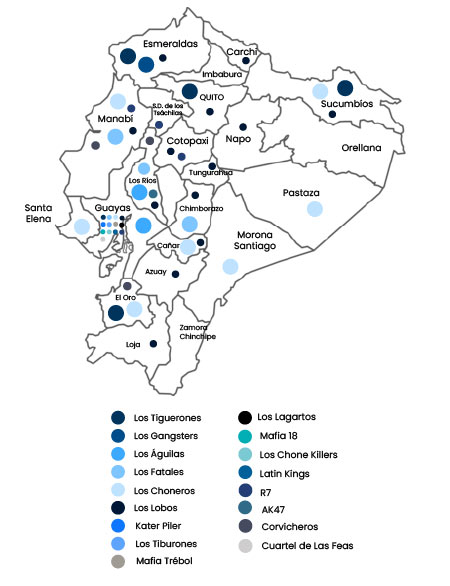

Ecuador has become one of the most critical and visible epicenters of the fourth Wave of transnational crime. Previously considered peripheral to drug trafficking routes, it now hosts a complex network of global criminal alliances. Two of Mexico’s most powerful cartels – Sinaloa and the Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG) – have established an active presence, competing for routes, ports, and local alliances. Joining them is Brazil’s Primeiro Comando da Capital (PCC), one of the most violent and organized groups in the region, along with the Albanian mafia, Turkish networks involved in chemical precursor and arms trafficking, and at least six Colombian Organized Armed Groups (OAG). According to Insight Crime, these groups operate through more than 17 Ecuadorian criminal structures.

This scenario is no accident. Ecuador offers ideal conditions: strategic location between Colombia and Peru, an efficient port network, porous borders, vulnerable institutions, and a fragmented state. These characteristics make it a prime logistical platform for global illicit economies.

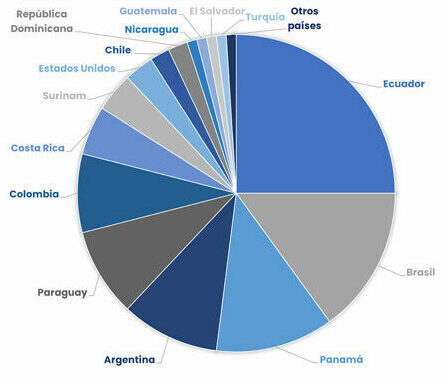

The situation is so critical that, according to the 2023 World Drug Report by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), Ecuador has surpassed Colombia and Brazil as the main cocaine exit point to Europe. This situation reflects the criminal networks’ logistical capacity and a significant shift in international trafficking routes, favoring territories with low state control, high corruption, and direct access to global markets. Ecuador is no longer a transit zone; it has become a global distribution hub – a strategic node on the new criminal map.

Cocaine seizures in Europe by country of origin, 2021

Urban violence, targeted killings, mafia infiltration into political, customs, and port structures, and the collapse of the prison system are signs of an ongoing war for territorial control in streets, prisons, and maritime corridors. Ecuador is not just a mirror of regional decline; it is the clearest warning of what happens when transnational organized crime colonizes the state from within.

Colombia is also transforming from a traditional cartel to a globalized crime.

Colombia, historically the epicenter of narcotrafficking in the region, is undergoing a silent but profound mutation. It is no longer just a producer and exporter of cocaine. It is now a convergence and battleground for multiple foreign criminal organizations that have adapted to local dynamics and are reshaping transnational crime through new alliances, logistics, and territorial control.

Recent reports from the Ombudsman’s Office and Revista Semana estimate nine to 15 foreign criminal structures operating in Colombia. Among them:

- Mexican cartels, including the Sinaloa, CJNG, and Los Zetas, not only purchase cocaine at its source but also deploy field operatives to secure production sites, control trafficking routes, and form alliances with OAG.

- Italian mafias (‘ Ndrangheta, Camorra, Cosa Nostra) possess the financial, political, and logistical capacity to connect Andean cocaine to European markets.

- Balkan cartels, known for their brutality and efficiency, specialize in maritime trafficking and distribution across Eastern and Central Europe.

- Turkish networks involved in chemical precursor and arms trafficking maintain ties to power structures that ensure impunity.

- Possibly, the PCC from Brazil has demonstrated regional ambitions across South America.

The classic Colombian narcotrafficking model, based on vertical structures and exclusive territorial control, is giving way to a new shared criminal ecosystem, where multiple actors coexist, compete, and collaborate. The logic of “exclusive turf” has been replaced by functional agreements, temporary alliances, and strategic fragmentations, governed less by hierarchy and more by network dynamics.

On this new criminal chessboard, conflicts are not only between local groups like FARC dissident groups, the ELN, or Los Caparros. Global mafias now wage discreet wars over strategic corridors, urban centers, river and sea ports, clandestine routes, and logistical hubs. Cities like Buenaventura, Tumaco, Cartagena, Barranquilla, and Cúcuta have grown in importance as nodes in international trafficking networks, and have seen increased violence linked to territorial control and money laundering.

Colombia is not repeating the past. A new generation of organized crime, which no longer follows the patterns of the 1980s and 1990s cartels, is transforming the country. It operates under a transnational, corporate, and tech-driven model, where illicit economies merge with formal commerce. Moreover, corruption and institutional capture are not anomalies but rather strategic operational tools.

From traditional drug cartels to corporate-style narcotrafficking

Narcotrafficking is no longer a rudimentary business centered on cocaine and led by charismatic kingpins. Today, major cartels- especially Mexico’s Sinaloa Cartel and CJNG – operate as true global criminal corporations, adapting strategies to shifting drug demand and illicit economic trends. With declining cocaine use in the U.S. and the rise of synthetic drugs like fentanyl and methamphetamines, these groups have diversified their portfolios and built supply chains spanning Asia, Europe, and Oceania.

Drugs no longer move primarily by clandestine aircraft or speedboats. The scale of today’s business, driven by the need to supply new markets, requires a more complex and less detectable infrastructure: legal international trade. Drugs are now hidden among flowers, bananas, shrimp, or textiles, smuggled via shipping containers, cargo planes, and global supply chains.

This shift has made the export sector both a key player and a vulnerable target within the criminal scheme. Mafias increasingly depend on front companies, logistics operators, sanitary permits, and access to ports and airports to move tons of drugs undetected. To achieve this, they bribe officials, forge documents, infiltrate legal businesses, and pay off inspectors at critical control points.

Legitimate businesses face enormous challenges. They must protect their operations from being used as “corporate mules” and avoid reputational damage, commercial sanctions, and loss of international partners’ trust – even when they are unwitting victims. Internal audits, security controls, and compliance certifications are not just best practices but survival mechanisms in a criminally contaminated environment.

This phenomenon is especially acute in countries with vulnerable ports, weak state capacity, and criminal networks shielded by corruption and intimidation. Foreign trade – a legitimate development driver – is hijacked by a transnational criminal system operating with corporate logic but without rules, ethics, or financial limitations, and with far more money than any state.

Therefore, the response can no longer rely solely on law enforcement. An active alliance between the private sector, the state, and international cooperation is required to secure supply chains, strengthen internal controls, and share early warnings. In this new phase of organized crime, business leaders are also on the front lines.

Crime and the state: a thin line

One of the most alarming aspects is growing state complicity. Farah warns that some governments are enabling these networks by action or inaction. This includes the uncontrolled flow of chemical precursors from China and the explicit protection some regimes offer criminal groups for political gain.

Added to this is the regional failure to share intelligence effectively. International cooperation remains mired in distrust, bureaucracy, and ideological divides between governments.

Conclusion: all in the same storm

Conclusion: Everyone Is In The Same Storm

Latin America is experiencing an unprecedented transformation of organized crime. It is not just about narcotrafficking, but about global networks that blend illicit economies, hybrid structures, and increasing capacity to operate between legality and illegality with alarming efficiency.

Today, the business no longer revolves solely around the U.S. Europe, Asia, Oceania, and the Middle East have become new centers of demand. Routes have multiplied, products have diversified, and criminal groups have reached near-corporate levels of sophistication. What was once a regional phenomenon is now part of a global criminal architecture.

Ecuador is not an exception; it is a warning. The risk is not that it becomes Colombia. The real risk is that all countries – from Mexico to the Southern Cone – may resemble today’s Ecuador: a nation overwhelmed by criminal structures seeking routes, territories, institutions, and communities to control or co-opt.

In light of this reality, the response can no longer be fragmented, reactive, or ideologically driven. A coherent and sustained regional strategy based on agile intelligence sharing, dismantling financial networks, effective judicial cooperation, and institutional fortification is needed. This situation requires political will, deep reforms, and a public aware of the threat’s magnitude.

The issue is no longer whether one country will “become” another; it is about recognizing that we are all – to varying degrees – already in the same storm. And if we do not act with vision and resolve, that storm will destroy what remains standing.